Listen to me telling this classic Christmas ghost story – “A Christmas Carol” by Charles Dickens. I have read this story on the podcast before (in episode 320) but it’s a good one so let’s do it again, shall we? 🎅

Listen to me telling this classic Christmas ghost story – “A Christmas Carol” by Charles Dickens. I have read this story on the podcast before (in episode 320) but it’s a good one so let’s do it again, shall we? 🎅

🎧 Learn English with a short story. 🗣 Listen & repeat after me if you’d like to practise your pronunciation. 💬 Learn some vocabulary in the second half of the video. 📄 I found this story in answer to a post on Quora.com asking about true scary stories. I thought I could use it to help you learn English. Can you understand the story, and predict the twist at the end?

The Invitation

About 7 years ago I got an invitation to attend a dinner party at my cousin’s house. I have a pretty large family and I had never actually seen this particular cousin before. I had only ever spoken to him on the phone. I was surprised that his family unexpectedly invited me over, but I was curious to finally meet them.

The invitation had an address that I didn’t know and the GPS was unfamiliar with it too. It was in one of those areas where Google Maps doesn’t work properly because of poor phone reception,

so I had to use an old fashioned paper map. I marked the location on the map, tried to get a sense of where I was headed, and set off in my car.

As I was driving I started to notice how far I’d travelled into the countryside, away from civilization. I saw trees, farms and fields passing by. Just trees, farms, and fields, and more trees, more farms and more fields.

“Where the hell am I going?” I thought to myself. I’d never ventured out so far in that direction before.

I drove for quite a long time, trying to locate the address I had marked on the map.

The thing is, in this area, a lot of the roads don’t have names, or the names aren’t clearly marked by road signs. I just had to try to match the layout of the streets, to the layout I could see on the map.

I finally found a place at a location that looked like the one I had noted on my map. I was pretty sure this was the right spot, so I parked and got out of the car.

Approaching the house I noticed how dull and dreary it looked. It was completely covered in leaves, branches and overgrown trees.

“This can’t be it.” I said to myself.

But as soon as I walked onto the rocky driveway my aunt and uncle came out to greet me. They seemed excited and welcoming.

“Hello! Hello! Come in! Come in!” they said, beckoning me inside.

Walking into the house, I asked where my cousin was. Answering immediately one of them said, “Oh, he just went to run a few errands. He should be back later.”

I waited in their kitchen and we spent a couple of hours talking about my mother and my family. My aunt made a delicious homemade pot roast that I finished off in minutes.

After dinner we played an enduring game of Uno. It was surprisingly fun and competitive. My aunt in particular seemed delighted to be playing.

When we finished the game of Uno it was almost dark and there was still no sign of my cousin. My aunt and uncle assured me that he’d be back any time soon. Despite what they said, I decided that I had to leave.

It was almost dark outside and I knew it would be a nightmare to find my way out of this dreadful place after sunset, with no streetlights or road signs. As my GPS just wasn’t working, I asked my aunt and uncle the most efficient way to get to the highway.

They gave me a puzzled look.

“But, we thought you were staying the night?” they said.

I told them I couldn’t because I had work the next day and couldn’t afford to miss another day. “It’s much better if you leave tomorrow morning. Trust us. You’ll get lost” they said.

I shrugged it off and told them not to worry,

“Don’t worry. I’ve got a pretty good sense of direction. I could find my way out of the Sahara desert.” I told them.

Looking aggravated, they strongly advised me to stay the night for my own sake. Their body language was weird too as they became more serious and insistent. My uncle stood shaking his head, and my aunt began to move about the place, picking up a set of keys to unlock what I assume was a spare bedroom.

At this point I was getting annoyed and irritable. I sighed, “Fine I’ll stay the night then, but I have to get up very early for work.” I said. Both of them seemed strangely ecstatic that I was staying the night.

As soon as they went out of the room to get bed sheets and pillows,

I ran out of the door, got in my car and hastily pulled away. I know it was rude, but I suddenly felt the urge to get out of there, quickly.

It seemed to take me ages, but I finally found my way back to the main highway and drove back through the night, wondering why my cousin had never turned up.

I got home several hours later than I expected. It was after midnight and I didn’t want to wake my parents up. Climbing over my fence and entering the back door, I noticed that the kitchen lights were on.

As soon as I took my first step through the door, I saw my mom sitting there looking impatient.

“Where have you been?”

She asked.

“I was at aunt Debra’s. I told you.”

I replied.

“Then why did she call saying you never arrived?”

To this day, I still have no idea who I visited.

Read the original version on Quora.com

This is the longest episode of LEP so far, and it’s a solo ramble. Relax, follow my words, hang out with me for 3 hours, get stranded on a desert island of the imagination, and then get rescued. Includes a haircut, a sleep and a t-shirt change during the episode.

Reading an article by Gavin Lamb (PhD) about the conclusions of academic studies into language learning, and adding my own reflections and comments. What does research tell us about the best way to learn a language? What are the most important things to consider? What are the best methods? The article boils it all down to three main points.

Join me as I read through a bizarre online game. Have you ever wondered what it would be like to be a lemon? No? Well, neither had I, until I played this game. Can I escape the kitchen, become human again and avoid being chopped up and turned into a juice! Watch out for some descriptive language and some funny moments along the way! Story by Daniel Champion on www.textadventures.co.uk

Let me read you a classic Sherlock Holmes detective story, by Sir Arthur Conan Doyle. I’ll read the original text and stop regularly in order to explain what is happening.

In this final part of the series I’m going to evaluate ChatGPT’s ability to work as a dictionary with definitions, example sentences, synonyms, phonetic transcriptions, etc. I test its ability to convert texts into British English or other varieties, see if it can help with sentence stress and word stress, and check its ability to create grammar and vocabulary quizzes and other useful exercises.

Hello listeners,

This is the 3rd and final part of this little series of episodes I’ve done about using ChatGPT to learn English.

I’m experimenting with lots of different prompts to see if it can do things like:

In this part I’m going to try to answer these questions:

You can get a PDF of the script for this episode which includes all the prompts I am using to get ChatGPT to do specific things.

Check the episode description and you will find a link to my website page where you can get the PDF scripts for parts 1,2 and 3 of this series.

If you are watching on YouTube I recommend using full screen mode so you can read the on-screen text more easily.

OK, so without further ado, let’s play around with ChatGPT a bit more and see how it can help you learn English.

Ask it to define words

What does “rambling” mean?

It gave pretty good definitions I have to say.

Arguably it’s not as good as a proper dictionary.

Just type the words into a dictionary and you’ll get way more info, including parts of speech, pronunciation, example sentences, related phrasal verbs etc.

But having said that you can ask ChatGPT for more specific details about words, including:

Etymology

What is the origin of the expression “break a leg?”

Create mnemonics to help you remember vocabulary

Can you create some mnemonics to help me remember these words and phrases?

ramble, waffle, meander, go off on a tangent, get sidetracked

It did it, and I must say this is pretty impressive.

You still need to use your imagination a bit, but these mnemonics are certainly a good starting point.

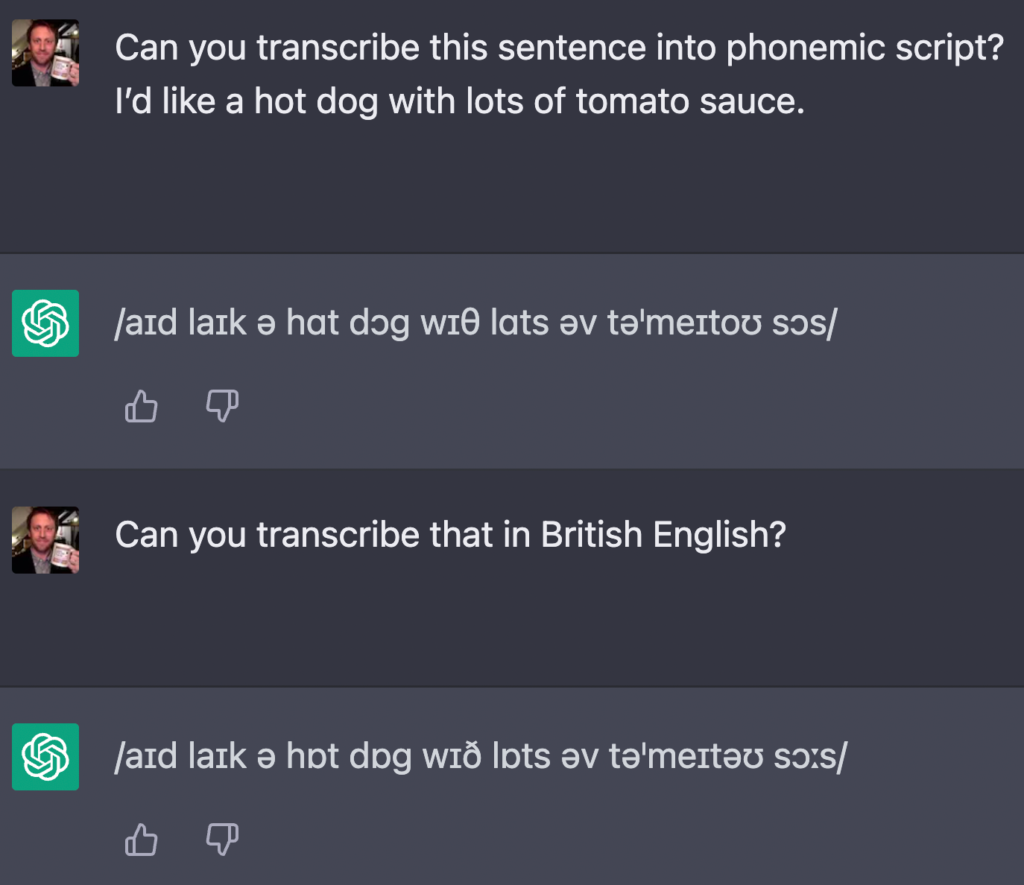

Ask it to transcribe things into phonemic script

But only in standard American?

Is it good at transcribing things in British English?

Can you transcribe this sentence into phonemic script?

I’d like a hot dog with lots of tomato sauce.

Different versions of the language

Can you convert this story into (insert dialect here)?

This is a paragraph I came up with which contains loads of words that are different between US and UK English.

Let’s see if it can convert this UK version into US English.

First I’ll read it out. See if you can identify the words which will probably be different between US and UK English.

| I just popped out of my flat to get some post from the postman when I realised I had locked myself out. I was stuck outside with only a pair of slippers on and it was the middle of autumn. To make matters worse I really needed the toilet. My car was there but of course I’d left the car keys in the house as well, although I couldn’t see where they were because my curtains were closed. Then I noticed that some bloody yob had put a big scratch across the bonnet of my car. That made me really angry I can tell you. “You’ll be hearing from my solicitor” I said to myself. Just when I thought my day couldn’t get any worse the TV aerial on the roof of my house fell off and crashed into the windscreen of my car, smashing it to pieces. I thought “I’ll need to make a trip to the chemist for some medicine to help me recover from this!” I walked along the main road and on the way I stopped to get some chips from the fish & chip shop at the main crossroads near my house. When I had finished, I put the paper bag in the rubbish bin and walked under the flyover to the chemist’s. I got my medicine and headed home. Of course, I was still locked out so in the end I had to jump over the fence into my back garden and climbed into a window which I had left open. Luckily I lived on the ground floor so I didn’t actually need to climb up the wall or anything, but unfortunately I broke a mug which was on the window sill. I used my hoover to clean up the broken pieces. Suddenly I heard a siren and someone knocked at the door. “Oh no, it’s the old bill!” I thought. “They think I’m burgling my own house!” I went to answer the door, but I didn’t realise that I’d ripped my trousers climbing in the window. I opened the door and stood there with my trousers hanging open. They could see my pants and everything! How embarrassing! |

Make a funny dialogue between two friends in a pub in London speaking British English. Include a joke at the end of the dialogue.

Generate the same response but the two friends are from Belfast, in Northern Ireland.

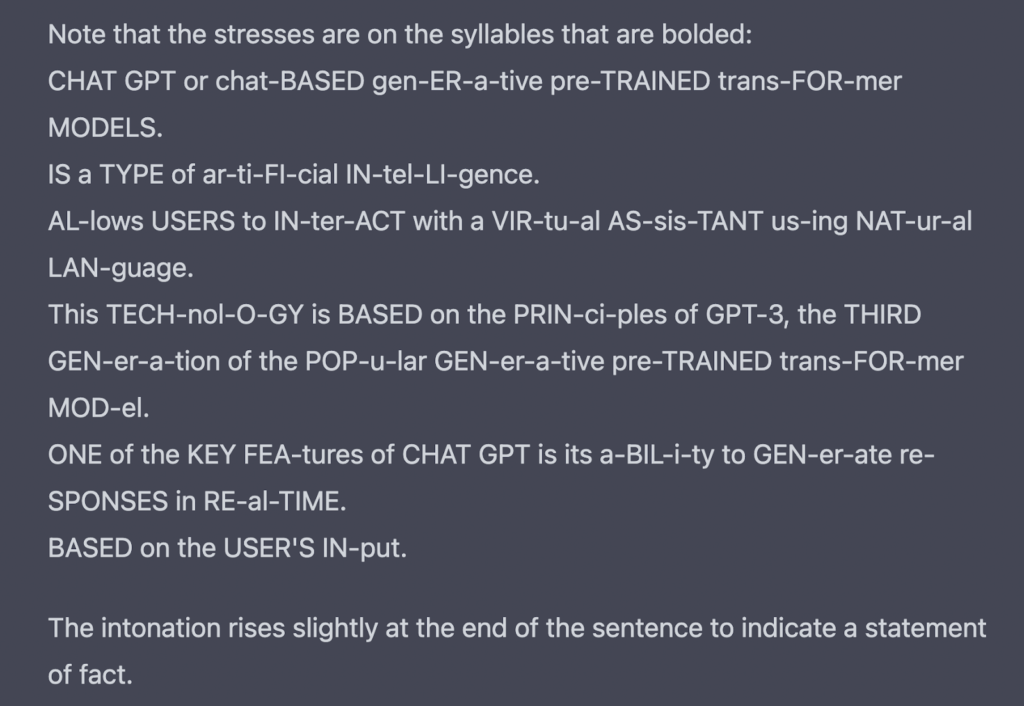

Sentence stress, pausing and intonation

Ask it to help you read out a text with the right pausing, stress and intonation.

Can you help me to read out this paragraph, showing where the pauses, stress and intonation should be?

Chat GPT or chat-based generative pre-trained transformer models, is a type of artificial intelligence that allows users to interact with a virtual assistant using natural language. This technology is based on the principles of GPT-3, the third generation of the popular generative pre-trained transformer model.

One of the key features of chat GPT is its ability to generate responses in real-time, based on the user’s input.

That is from an article about ChatGPT which I found on medium.com 👇

All you need to know about ChatGPT & Why its a threat to Google | by Deladem Kumordzie | Medium.

It’s good at showing where the pauses should be,

but it’s bad at showing word stress or sentence stress.

☝️bad bad bad bad bad! ☝️

Grammar or vocab quizzes or tests

Let’s ask it to create a grammar review test for upper-intermediate level.

Create a 10-question grammar test to help me practise English at an upper-intermediate level.

10 questions isn’t really enough to cover all areas of grammar but you would expect it to cover at least 10 different grammar points. Did it?

What happens if I ask it to make a 20-question grammar test for B2 level? Does it use a wide variety of forms? Does it require the test taker do demonstrate control over the language or is it just multiple choice?

The results are not as rigorous, complete, reliable or detailed as similar tests in published materials such as the diagnostic test at the back of English Grammar in Use by Murphy.

It’s also not focused on language that you have been studying in your course.

It always uses multiple choice.

Basically – it doesn’t produce a very reliable test.

Vocabulary review tests, to help you remember words and phrases

Create a vocabulary test to help me remember and use these words and phrases.

ramble, waffle, meander, go off on a tangent, crack on, Get away with, get by, get on with, get off on, get through to, get around to

The test it created was multiple choice and only contained definitions.

Definitions are good but not the best way to help you remember vocabulary. You need example sentences and it’s best if you have to use the words in a meaningful and contextualised way. At least give us example sentences with the words and phrases removed and ask us to put the correct words in the correct place, perhaps in the correct form.

But it’s better than nothing, and I think this could be useful if you have a list of words or phrases that you’re trying to remember.

Text adventure games to practise grammar

I’ve always wanted to create one of these but have never got round to it. One of the reasons is because it’s quite a time consuming task and requires a lot of patience to make sure I’m using plenty of good grammar questions and combining that with an interesting story with engaging choices. Maybe ChatGPT can cut out a lot of the work.

Create a 5 minute text adventure game to help me practise English grammar

Nice idea but it did a bad job. It ended up creating a game with virtually no grammar questions and then it played the game itself.

I’m sure there are other language practice exercises or activities which ChatGPT could do.

If you can think of some other things, put them in the comment section.

Ask it to adapt its English level to yours

You can write things like “please adapt your English to B1 level” or something similar.

Actually I just tested this with this prompt:

Give me some advice on how to set up a podcast studio. Please use A2 level English.

Also, this:

Can you adapt this passage from Hamlet by Shakespeare into elementary level (A2) English?

So you can ask it to use simple English at your level.

You can also prompt it in your first language of course, but you have to request that it responds in English.

Overview / Comments / Conclusions

It’s definitely way better than any chatbots I’ve ever seen before.

There’s no denying how impressive it is in many ways. I only scratched the surface here. It can do lots of other things including creating legal contracts, writing song lyrics, writing short stories, movie plots, essay plans, essays etc.

But I think we still need to be a bit sceptical or critical about it at this stage. It’s impressive at first, but working closely with it shows us its limitations.

Don’t assume that it is answering your questions correctly or reliably. It seems to miss things, and contradict itself sometime and also it lacks the overall vision and emotional intelligence that a good teacher can have.

There are also questions about things like how it could encourage cheating, and also other criticisms (I’ll explore some more in a few minutes).

They’ve done wonders with the marketing – allowing us all to use it freely, which has caused us all to talk about it and as a result it’s gone viral with everyone talking about it. This is helping them to make money now (by selling it as a service which people can incorporate into their websites etc, and charging people for the PRO version of it) and also it’s allowed them to get a lot more data (as millions of people have been using it) which is allowing them to develop it further. In fact it is improving and changing all the time, becoming more and more accurate and sophisticated.

For learning English, there are definitely ways it can help, including taking out some of the time-consuming things like creating little memory tests, creating sample texts and dialogues which you can use, having some limited conversation practise.

One of its main strengths is error correction. It can quickly correct errors in your writing and even explain the reasons, although the explaining is a bit limited.

It can correct your English, but don’t rely on it too much. Try to use this as a tool to help you improve your English, not just something that you rely on at the expense of making progress on your own. Learn from it, but don’t let it do all the work.

You need to have a pretty good level of English to prompt ChatGPT properly. Sometimes you need to find “clever” ways to get it to do exactly what you want and I think this requires a lot of control over your language.

As I mentioned before you often need to find different ways to ask your question or to give your prompt before you get what you’re looking for.

Remember you can tell it *exactly* what to do. So keep getting specific.

It’s still a bit early for us to completely rely on it as a personal language teacher or a conversation partner, but it can be a convenient tool for certain basic tasks that can be time consuming.

Chat GPT has no emotional intelligence. It isn’t great at working out what you really want it to do, which is something I have to do as a teacher all the time. I’m always interpreting my students intentions and what they want to say, and then helping them find the right words or sentences to do that, and then helping them produce that again and again, adapting and reacting all the time and also managing the students feelings and emotional responses. It’s a special kind of dance that you have to do with the student and this is extremely complicated and requires a lot of sensitivity and also plenty of teaching experience to allow you to pinpoint exactly what is needed of you as a teacher.

ChatGPT has a long way to go before it can do that.

For the time being it is no replacement for the interaction you can have with a real human and this is still one of the best ways to practise and develop proper communication skills in English. It is definitely better to practise interacting in English with a real human, preferably one who is able to help you with your English learning because they have skills and experience in this area.

Also, don’t underestimate the importance of those emotional aspects of communication with people. ChatGPT is no replacement for that, at the moment.

Maybe one day it will be so good that talking to it will be indistinguishable from talking to a real person, which is quite an unnerving prospect somehow.

But anyway, it’s important to continue practising your English by interacting with real people in social scenarios.

Talking to people can be a bit intimidating if you are shy or introverted, but it is essential to practise doing it because interpersonal skills are vital in communication.

ChatGPT doesn’t speak or listen yet, so no listening or speaking practice is possible, but no doubt that’ll come eventually.

What does ChatGPT say about its limitations as a language learning tool?

What are some possible problems with using ChatGPT for learning English?

Other issues

I wonder if it will be free forever. They’ve made it free now to get our attention but eventually we’ll probably have to pay to use it fully. In fact, already the free version is quite limited. It’s slow and stops performing after about 1 hour of interaction.

I wonder if later this year ChatGPT will still be as accessible as it is now. I expect they let us all use it for a while in order to get our attention and now they’re monetising the product and limiting free access to it.

I wonder how ChatGPT will develop. It will certainly get better and better.

Perhaps one day (soon) it will flawlessly do all the things we want it to do.

There are also some frightening aspects to this when we imagine the impact this might have on the world.

Despite what I said about it being no replacement for human interaction, it is remarkably advanced and sophisticated and that is only the current version of the software.

I expect this current iteration of ChatGPT is just the tip of the iceberg and eventually it will be almost impossible to differentiate between the chatbot and a real human.

And when this is combined with life-like speech generation and real life visuals (deepfakes) as well – a video version talking and responding naturally with a lifelike face and voice, in fact so lifelike that we won’t be able to work out if we’re dealing with a human or not, that will be quite frightening because suddenly then we’re living in the film Bladerunner, ExMachina or A.I. with all the ethical and social ramifications explored by those films.

By the way, those films seem to explore questions of whether it is ethical for us to create highly intellilgent AI capable of human-like emotions, and whether it is ethical for us to treat them like slaves or as sub-human. They are like us, even better than us in many ways, but they don’t have the same rights as us.

Other films have explored the threat to humankind of artificial intelligence. This includes things like The Terminator series and The Matrix which show a world in which AI becomes self-aware and decides to fight against humans or to enslave us.

A more immediate and realistic problem with something like ChatGPT is how it can affect the job market and whether it will make lots of people redundant.

What will we do when so much of our work can be done by AI that doesn’t need to eat, sleep, or take breaks? What will happen to us? Will people still be employable? What happens when the human population continues to rise, but the number of jobs we can do in order to earn money, decreases?

I have no idea.

And will AI eventually make it completely unnecessary to even learn another language? Will we simply have simultaneous automatic translations? Will AI augment our reality completely? Will we somehow be connected in the most intimate and integral way with technology, which will mean we won’t need to learn languages any more?

I’m not sure to be honest. What people usually say in response to that question is that we will always want to learn languages because there can be no replacement for the experience of communicating with people naturally using language and no technology can replace or replicate this experience sufficiently.

Let’s ask ChatGPT some more questions about itself, relating to things like people’s fears about it and if it will cause more cheating

What are people’s fears about how ChatGPT will change the world for the worse?

How might AI become a threat to humans?

Will ChatGPT help people to cheat?

Yes, probably. I can’t see how this won’t be a problem. I mean, this will almost certainly be a problem. Surely, students will just take the easy route and get ChatGPT to write essays for them, or other assignments. That’s obviously bad, because these students will not actually learn the skills and knowledge they’re supposed to learn during their studies and also it could compromise the effectiveness of education in general.

I don’t know how this problem is going to be solved. I don’t know how OpenAI have responded to this.

Let’s see what ChatGPT says about people using it to cheat in their homework.

Will ChatGPT help people to cheat in homework and academic essay tasks?

Will there be more cheating as a result of ChatGPT?

So it encourages people to cheat and it doesn’t know how people will use its services, but let’s be honest – it’s definitely going to result in more cheating.

It will be very interesting to see how ChatGPT and other software (because it’s not just OpenAI – there are loads of other competing companies also developing similar systems all over the world) It’ll be very interesting to see how this changes the world and of course we all hope that it changes things for the better and that it ultimately improves the human experience, making our lives better, allowing us to thrive.

That’s it – thanks for listening!

Leave your comments in the comment section.

I’m probably going to do another episode about ChatGPT just because it is fun to mess around with it and really see what it can do, including asking it to plan a podcast episode for me, write an introduction to an episode, have funny conversations, write jokes and short stories and lots of other things.

🙏

My friend Anna has written a book for children (7+) which has a full publishing contract and is available in all good bookshops now. The book tells the story of a boy who accidentally creates a monster when his secret collection of nose bogeys gets struck by lightning! This conversation includes lots of talk of snot and bogeys, as well as stories from Anna’s time as a travel writer.